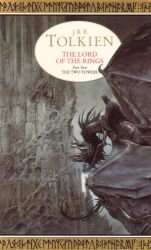

Another week, another chapter of the Lord of the Rings re-read. Today we’ll consider chapter III.7 of The Two Towers, “Helm’s Deep.” Book-wide spoilers and comments after the jump.

What Happens

The Riders head toward the fords of the Isen, camping overnight, and are found by a single Rider who says they were driven away from the Isen by Saruman’s Orcs and the wild men of Dunland, and though Erkenbrand had collected some men and headed for Helm’s Deep, the rest had scattered. The man says that to tell Éomer to go back to Edoras, but Théoden comes forward and tells the man that they ride to battle. Gandalf tells them to go to Helm’s Deep, not the fords; he will meet them there.

The Riders arrive at Helm’s Deep that night, and a large force attacks. Aragorn and Éomer rally the fighters against a first attempt to destroy the gates of the Hornburg, a tower barring the entry to the Deep, and Gimli saves Éomer’s life. The assault continues: Orcs sneak under the wall connected to the Hornburg through a culvert, which is unsuccessful, but then blow up the culvert and rush through, which is successful. The Orcs take the wall across the Deep; Éomer and Gimli are separated from Aragorn and Legolas in the fighting. Théoden resolves to ride forth at dawn.

When he does, he cleaves a path through those blocking his way with no trouble, for they are staring away from him at a forest that appeared overnight. Trapped between the Riders, the forest, and the newly-arrived Gandalf and Erkenbrand, the wild men surrender and the Orcs flee into the forest, never to come out again.

Comments

I don’t know why, but I have a horrible time keeping track of what’s going on where in this chapter; yes, even reading slowly and making an effort. So I was pleased and grateful to find a useful map of Helm’s Deep, halfway down this page; I downloaded the image, put it on my PDA, and went back and forth between it and my e-book. If anyone else out there has this problem with this chapter, I highly recommend it.

* * *

Before we get to Helm’s Deep itself, a logistical issue: the Riders are riding traveling swiftly because “Forty leagues and more it was, as a bird flies, from Edoras to the fords of the Isen, where they hoped to find the king’s men that held back the hosts of Saruman.” And I stopped reading and said, “They did?!”

I went back and looked, and I couldn’t find any mention of those men or the Riders’ goal of finding them holding back Saruman’s forces. Was I the only one? Or is it this chapter—there’s a not dissimilar logistical issue at the end, which we will get to in due time.

Finally, does anyone have access to an OED? “Bivouac” sounds distinctly anachronistic to my ear, but that’s just instinct.

* * *

Okay, there are three main things I want to talk about with regard to Helm’s Deep proper: the metaphorical language used about the battle; the warrior perspective, for lack of a better description; and the Dunlanders.

First up, the metaphorical language, which is overwhelmingly drawn from nature.

- The gathered Orcs and Dunlanders are consistently referred to as an overwhelming body of water: a “dark tide” that “flowed up to the walls from cliff to cliff”; charging and advancing “like the incoming sea” (against “a storm of arrows” and “a hail of stones”); “the hosts of Isengard roared like a sea” (in which the Hornburg is “an island”); “the last assault came sweeping like a dark wave upon a hill of sand.”

- The Orcs are twice compared to animals (“apes in the dark forests of the South” and “rats”). Once the Orcs and Men together are compared to “swarming flies.” The Dunlanders may also have a solo animal comparison when Éomer says their voices “are only the scream of birds and the bellowing of beasts to my ears,” depending on how you want to count that.

- Aragorn desires before the battle to “ride down upon them like a storm out of the mountains.” When the King’s company rides out at dawn, “they drove through the hosts of Isengard as a wind among grass.”

I don’t have any conclusions about this, but it really jumped out at me.

* * *

Second, the warrior perspective. I mean two things here, which may not actually fall under the same category but evoke the same reaction in me: Gimli and Legolas’s competition over their number of kills, and the Riders cleaving their way to the Dike through an unresisting and facing-away crowd.

Between my last re-read and now I’d seen people say that they couldn’t bear Gimli and Legolas’s competition in this chapter, which is something I hadn’t thought about until then. Now, well, the best I can say is that I cannot reconstruct the mindset that treats causing other people’s deaths as a rather light-hearted competition. I thought perhaps it was black trenches humor, but I do not get that impression from the text; instead it feels like some kind of pre-modern warrior tradition that I simply cannot connect with.

Then there’s the riding out from the Hornburg, which is clearly meant to be grand and heroic:

And with that shout the king came. His horse was white as snow, golden was his shield, and his spear was long. At his right hand was Aragorn, Elendil’s heir, behind him rode the lords of the House of Eorl the Young. Light sprang in the sky. Night departed.

‘Forth Eorlingas!’ With a cry and a great noise they charged. Down from the gates they roared, over the causeway they swept, and they drove through the hosts of Isengard as a wind among grass. Behind them from the Deep came the stern cries of men issuing from the caves, driving forth the enemy. Out poured all the men that were left upon the Rock. And ever the sound of blowing horns echoed in the hills.

On they rode, the king and his companions. Captains and champions fell or fled before them. Neither orc nor man withstood them. Their backs were to the swords and spears of the Riders, and their faces to the valley. They cried and wailed, for fear and great wonder had come upon them with the rising of the day.

So King Théoden rode from Helm’s Gate and clove his path to the great Dike.

(Emphasis added.) And I make a face because my heroes just killed a bunch of people from behind. Would this really have been not just acceptable but heroic behavior to the Anglo-Saxons, or any other historical culture that the Rohirrim might have been modeled on?

* * *

Finally, the Dunlanders. Gamling says the Dunland tongue

is an ancient speech of men, and once was spoken in many western valleys of the Mark. Hark! They hate us, and they are glad; for our doom seems certain to them. “The king, the king!” they cry. “We will take their king. Death to the Forgoil! Death to the Strawheads! Death to the robbers of the North!” Such names they have for us. Not in half a thousand years have they forgotten their grievance that the lords of Gondor gave the Mark to Eorl the Young and made alliance with him. That old hatred Saruman has inflamed. They are fierce folk when roused. They will not give way now for dusk or dawn, until Théoden is taken, or they themselves are slain.

Note, first, that Gamling is wrong: the Dunlanders do surrender.

Second, again we have my approaching the text from a completely different perspective than Tolkien. Because you say “someone who didn’t live here gave the land away to newcomers” and I say “colonialism, imperialism, and the oppression, forced displacement, and genocide of native peoples.” In other words, I doubt that the text wants me to sympathize with the Dunlanders—no-one in this chapter, at least, acknowledges that they have a legitimate reason to be upset—but you bet I do.

I think this is the point where I must add the ritual disclaimer about intent: no, I’m not saying Tolkien was an Eeeeeeevil person or that he consciously sat down and said “I’m going to create a world that echoes and perpetuates real-life injustices! Yay!” I am saying that he and I bring very different perspectives to the social situations in the book and that those differences mean that my sympathies are not aligned with the text’s. Further, I think it’s important to point out the assumptions and parallels in the text because (1) it’s part of a close reading, which is what I’m doing here and (2) stories influence the way we see the world, and if we don’t stop and examine the unspoken assumptions in stories, we’ll never be able to identify the present-day mindsets that support injustices.

* * *

Back to logistics. Do we know where Erkenbrand was? If I have the timeline right, he was at least half a day behind Théoden in getting to Helm’s Deep, and while he was starting from further away, no-one seems to think it unreasonable that he should have arrived at the same time as, or even before, Théoden. I skimmed ahead a bit and checked Appendix B, but didn’t see anything. (I also can’t remember what Gandalf was doing, but I feel more confident that that, at least, will be answered.)

On a minor note, should there have been messengers or something during the battle, so that Aragorn and Éomer don’t have to rely on their ears and a chance flash of lightning to notice the battering rams advancing on the gates, or on Gimli yelling that to discover that the Orcs are behind the wall?

* * *

I sound awfully cranky about this chapter, so I’ll end on two things I liked:

- “And then, sudden and terrible, from the tower above, the sound of the great horn of Helm rang out.”

- The revelation of the forest, which was just the right amount of strange and non-human to jolt me out of the battle and into wider considerations.

« Two Towers III.6 | Index | open thread »

Kate Nepveu is, among other things, an appellate lawyer, a spouse and parent, and a woman of Asian ancestry. She also writes at her LiveJournal and booklog.

OED sez:

Bivouac: “Originally, a night-watch by a whole army under arms, to prevent surprise; now, a temporary encampment of troops in the field with only the accidental shelter of the place, without tents, etc.; also the place of such encampment.”

-first usage as a noun: 1706

-first usage as a verb (with the latter meaning): 1806

Brust’s books (specifically Dragon, I think) talk about troops being bivouacked. I think that Dumas has it as well.

Would this really have been not just acceptable but heroic behavior to the Anglo-Saxons, or any other historical culture that the Rohirrim might have been modeled on?

Definitely acceptable. War is, after all, war; and battles aren’t exactly chivalrous. Tolkien actually condemned the only example of express chivalry in battle I can recall off the top of my head; he thought the Anglo Saxon commander at the Battle of Maldon was wrong to give up the causeway as demanded.

Also, in this case the fleeing enemy is mostly made up of Orcs, and in the book’s reality, they simply cannot be considered human. They are indisputably evil. They are monsters, and chivalry does not extend to monsters.

The Rohirrim are likeable for a warrior culture, but Tolkien’s heart in these matters is probably closer to someone like Faramir (or Aragorn himself) for whom war is an unfortunate means to an end, not glory itself. I don’t think we’re supposed to approve everything they do.

Later Ghan-buri-Ghan will ask as part of the price of his help that the Rohirrim not hunt his people (noble savages to the point that Tolkien later gave them a history in the First Age and Numenor without having them partake in any of the bad stuff) like beasts. It’s pretty clear that the Rohirrim aren’t faultless in their dealings with others, and even from Gamling’s words I think the Dunlendings’ case is made pretty clear.

On the other hand, the Dunlendings also aren’t historically faultless– they apparently settled the province that would become Rohan after Gondor was established, and without the consent of the Gondorians (which at least makes the question of who the colonizers are a little more complicated). And, well, five hundred years. (There are advantages to at least being able to back-burner a territorial dispute after a while, whoever’s right.) Gamling in any case seems to be speaking more descriptively than prescriptively: they have this grievance which explains why they’re on the other side, and why he doesn’t think they can be dissuaded short of unambiguous defeat.

It’s a level of the war that’s more realistic and less epic. Tolkien gives enough information to let the reader see that the people of Dunland aren’t monsters, but human enemies with understandable (if not immediately resolvable) grievances. Similarly, there’s no lighthearted contest to kill the most Dunlanders (which probably puts the Rohirrim ahead of their historical models).

I’ve always seen the last charge to be a desperate, fey maneuver, a way to go out with honor and glory rather than be overwhelmed during a siege. If, in doing so, the enemy is unnerved and turns to flee — well, heck, that’s just the reaction you want, and of course you cut them down from behind.

I’ve also always thought that “their backs were to the swords and spears of the Riders, and their faces to the valley” because they were fleeing before the charge (as the previous sentence implies) — and it’s only *then* that Saruman’s forces see the mysterious forest and get *really* demoralized. If the sequence is the other way around (everyone’s staring at the forest and therefore surprised when they get speared from behind), then I agree it’s a bit less heroic.

OK, this:

Captains and champions fell or fled before them.

Combined with this from the previous graph:

Behind them from the Deep came the stern cries of men issuing from the caves, driving forth the enemy.

Causes me to read this scene very differently then you are. I think the combo of the dawn and the revelation of the weird forest AND the sudden kamikaze press of the Rohan are routing the enemy. Yeah, they are stabbing them in the back, because the enemy is trying to run away. And while I am no expert on the subject, I am fairly confident that just letting your enemy run away would not be a satisfactory resolution to the Anglo-Saxon mentality.

I was quite surprised to come here and find criticism, because this has always been my absolute favorite part of LoTR. It is almost, to me, as if the rest exists to support this part of the story.

It is fantasy battle well handled, in a plausible way. I need to remind myself from time to time that most people who read fantasy lack my extensive study of military history, and so have little idea what can be considered “realistic” in a fantasy setting. It is of course just MHO, but this seems what it would really be like. And as to the Rohirrim as elitist conquerors, well, the whole book is about a class of tall, fair skinned elitists trying to regain their lordship over the rest of mankind in western Middle Earth ;-) That’s why people in Russia, for example, have written The Black Book of Arda, to tell the other side of the story :-)

Keeping score is

a) similar to fighter pilots keeping score

b) keeping track of how many nonhuman monsters you’ve offed. Kinda like how many birds you hunted. Also,

c) similar to Plains Indians counting coup.

Bivouac is still used to refer to overnighting in the woods, not comfy in the barracks, by US military types.

I’m not sure as to the accuracy of that map. For one thing, the Hornburg is on the north side of the valley, not the south, and I always had the impression that the coombe opened eastward, though I can’t seem to find conclusive evidence for it.

Which way did everyone else think it faced?

Because you say “someone who didn’t live here gave the land away to newcomers” and I say “colonialism, imperialism, and the oppression, forced displacement, and genocide of native peoples.” In other words, I doubt that the text wants me to sympathize with the Dunlanders—no-one in this chapter, at least, acknowledges that they have a legitimate reason to be upset—but you bet I do.

Kate,

Originally with nothing to go on but my own intuition (slightly augmented, years later, by letter excerpts, quotes and analyses (er, none of which come to mind, so take all I say with the proverbial grain)), I’ve always read those passages in precise opposition to yours.

I see it as one of those moments when Tolkien reminds us (whether by artifice or accident I really don’t know – though I’d like it to be by design!) that his world is complicated. Gamling is a product of his culture, not an omniscient narrator, as I think Tolkien deliberately juxtoposed a few chapters later, when Rohan agrees that no one will “hunt” the Dunlanders again.

At the very least, you have to credit J.R.R. for realizing there was a not-Sauron-related conflict there.

All I can say about the controversial stuff is: I understand why you feel that way.

What Tolkien would say the Rohirrim lacked was a higher level of what he might have called “civilization”. They are rough, they are brutal, they fight on the side of good but they are emphatically not perfect.

But when they fight, they fight whole-heartedly, and that is a vital aspect of why they win. The Rohirrim battle scenes (the charge onto Pelennor Field even more than this) have fooled many readers into thinking Tolkien glorified war, but much else shows that he did not. He did think, however, that moping around or regretting your actions in the middle of a battle was neither an appropriate nor an effective way of expressing misgivings about war.

Lastly: I found the geography in this chapter confusing on early readings too.

Bivouac is still ordinarily used in French, mostly for mountaineering. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bivouac_shelter

I also can’t remember what Gandalf was doing, but I feel more confident that that, at least, will be answered.

He searched for Erkenbrand and made sure that he came to Helm’s Deep with as many men as he could gather. And he probably asked Treebeard to send his forest of Huorns.

First, bivouac is definitely anachronistic. The earliest recorded use is French from 1702 and it only entered English during the Napoleonic Wars. OTOH, the word itself does have Germanic (Swiss/Alsatian) roots in biwacht meaning “double guard”, i.e. night watch.

As for the battle, I’ve never really looked at it as anything other than heroic before. I can see what you are saying, but I do have a couple of comments. Gimli and Legolas’ game: This started out as a bit of warrior braggadocio before developing into a competition. Their focus seems to be primarily on orcs and can certainly be traced back to centuries and millennia of cultural and personal enmity.

Rohirrim v. Dunlendings: As others have pointed out, the Dunlendings were not entirely without fault here. I see the settlement of Rohan not as a colonial action. Rather Gondor settled them there as a buffer against the hostile Dunlanders. The migration of the Rohirrim is nothing like the colonial voyages of the modern Europeans. It is more to be compared to the vikings settling in Ireland or France or to the wanderings of the Germanic tribes into Roman territory at the end of the western empire.

The charge: This was originally intended as a suicide mission. The battle was perceived as lost. Theoden only hoped to take as many enemies as possible with him and die gloriously. When the enemy broke and fled, there seems to have been a bit of… exuberance on the part of the Rohirrim. And, yes, the Dunlanders do for the most part surrender.

As for Gandalf, he will explain in the next chapter that he spent the 2 or 3 days since he left the Riders visiting Treebeard at Isengard and searching for Erkenbrand and his scattered men.

First, the logistics. Theodred died defending the fords, but i assume the battle was still won, in that the fords were held. Otherwise the plains of Rohan would already be overwhelmed before Theoden rode out, and Gandalfs party could never have reached Edoras unopposed. Thus Theoden would expect to find a force of riders there, presumably with Erkenbrand in command after the fall of Theodred.

As for the battle, I agree with whoever said its the most strategically sound battle in the books.(Exept for the fact that it should never have happened; Putting the best cavalry in the world, outnumbered, behind walls seems rather stupid when you have the whole wide expanse of Rohan to harry the enemy. Feel free to correct me on this, no expert.)

And the most plausible part of it is that superior morale won the battle. The orcs were surprised by the appearence of the trees, and the sudden onslaught by the riders, and so lost their nerve and fled. This would have been a really stupid time to stop the charge and let them get reorganised, because as i read it, the riders were still soundly outnumbered, even with Erkenbrands reinforcements.

In regard to the dunlendings, I read Gamlings comments as rather regretful, and a way to show that there are two sides to this conflict.

I have much more problem with how the dunlendings are treated in the general mythology, where once again blood seems to matter very much:

The original keepers of Isengard were gondorians who fell from grace when they intermingled with the dunlendings.

And the most notorious bad guy in rohans history was Freca(i think), who’s sons started the civil war that ended the first line of markian kings and left Rohan open for orcish incursion from the mountains of mist.

This was the chapter that stopped me cold when I first read it back when I was 12 – stopped me so cold that I didn’t return to reading the book for months, a first for me, the book devourer. Because for me, it was utterly dull, and like you, I had a hard time following what was going on.

It still stops me in most rereads, to the point that now I tend to skim over or skip it entirely.

The one thing, oddly, that did grab my attention was Gimli and Legolas’s competition. I currently take it as an authorial way to free the reader from the otherwise endless heavy battle language. The story distinctly moves here from travel/adventure epic to war story, and while that’s certainly in the medieval tradition, it does require some – what’s the word I’m searching for? Overlay? Bridging? – to connect the tones of the differing chapters.

Still, probably hands down my least favorite chapter in all three books.

One of my problems with this battle is the depiction of the defensible qualities of the place. I don’t see why they built such a convenient ramp for the battering ram. That’s what drawbridges were for. They have this nice elevated roadway, but then no way to keep enemies from using it as a launching ramp.

euphrosyne @@@@@ #1: thanks for the OED on “bivouac.” I thought it sounded relatively modern.

tapsi @@@@@ #3, the problem is that so far I’m not convinced that Orcs are inherently and indisputably evil. Gimli, at least, knows that they’re intelligent and have personalities (based on his people’s stories of the attempt to retake Moria). But we’ll have more to say about this as we go.

Michael S. Schiffer @@@@@ #4, where’s the history of Ghan-buri-Ghan’s people? Or the timeline for the Dunlanders?

(I just checked and the _Silmarillion_ does have an explicit statement that the Numenorians really were divinely appointed to rule, which is also as you might imagine not something I have a lot of intrinsic sympathy for, or even within the created mythology considering how poorly the Valar treated Men (sic).)

*** Dave @@@@@ #5, CyricPL @@@@@ #6, I read it as some fleeing from the people formerly in the caves (which would be behind the wall and the King’s charge) and some staring at the forest as the sun rises, but it is ambiguous, looking at it again.

On the other hand no matter which it is, I still find the very heroic language incongrous, especially from someone who saw actual combat.

Marc Rikmenspoel @@@@@ #7, I was surprised to be critical! Before now this entire book, the first half of _TT_, was my favorite part of the trilogy.

Tell me about the Russian Black Book of Arda?

sps49 @@@@@ #8, but fighter pilots are at a distance, not cutting off people’s heads with their axes or killing them with knives; see my response to tapsi; and counting coup was about demonstrating skill by touching an enemy _without hurting them_.

other alias @@@@@ #9, I admit I suck at orientation, but I found that map useful in the general relationship of things to each other. (When people give east-west directions I have to stop and translate them into left-right, and then hold up my hands to see which way left is.)

ed-rex @@@@@ #10, very true that this is a not-Sauron related conflict. And if you read it as Tolkien expressing sympathy for the Dunlanders, then that’s good to know.

DBratman @@@@@ #11, I’m so relieved that you found the geography confusing too! And yes, it was my general impression about Tolkien’s treatment of battle, juxtaposed with the language that was used here, that was giving me cognitive dissonance.

birgit @@@@@ #13, yup! Gandalf’s errand is revealed in the next chapter.

DemetriosX @@@@@ #14, it’s true that Gimli seems to have been in only a position to be fighting orcs; Legolas was using his bow so it’s less clear about that.

I had forgotten that (per Appendix A) the Rohirrim were given this land as a reward after joining Gondor in a battle, and hadn’t showed up and then Gondor said “hey, keep it”–which is the impression that I got from this. I can’t quite tell if the Dunlanders were supposed to be hostile to Gondor from that bit, however.

sotgnomen @@@@@ #15, oh, of course, excellent point about the fords still being held. Thanks. And yes, it was Freca, upon further reading of Appendix A.

MariCats @@@@@ #16, I definitely found it a relief when we got a brief snipped of a couple of soldiers talking this chapter, and a return to Gimli and Legolas last chapter, so there’s definitely something to the use of those characters to shift or break the mood, especially since we’ve shifted so far away from where we started. (Hobbits next chapter!)

MKUhlig @@@@@ #17: I don’t see why they built such a convenient ramp for the battering ram. . . . what a good question.

Flicking through “The Wars of the Roses” by John Gillingham cutting down your enemy as he flees is pretty much par for the course in the middle ages

Tewkesbury (1471) “Once it was all over Edward gave his soldiers the freedom to pursure their enemies, capture kill and despoil them”

Siege of London (1471) “As they fled … several hundred were killed and more captured”

Towton (1461) “The battle itself had been evenly matched; the pursuit turned into carnage”

And so on. Its at the end of the age of chivalry rather than the begining but I don’t imagine earlier times were any different.

It is important to remember that Tolkien had experience of battle himself, in the trenches during the First World War.

“Bivouac” is a term that was in current use by the British and US militaries during both world wars, and by the Boy Scouts. Of course, the Scouts were founded by a militarist, racist, and sexually rather odd person.

I read LoTR first as a teenager, living in Jamaica, and the colonialist element of the blond Rohirrim versus the dark-haired Dunlendings was something that struck me. What I found most interesting was the objection to ethnic and racial mixture that crops up. Not just the mixing of human ethnic groups (as between Rohirrim and Dunlending) but also the horror at the possibility that the “blood” of human and orc had been blended by Saruman.

As a person of mixed heritage I do tend to note these things. It is worth pointing out that a middle-class Englishman of Tolkien’s generation would have found the idea of racial and cultural mixture rather abhorrent (see, for an example, Ian Fleming’s depictions of such).

While I am a huge Tolkien fan, you guys have hit on something that has always made me squirm about both his and Lewis’ writing-the repeated reference to inferior/superior race. The thing that softens the rub for me is that it’s ultimately the short, not particularly fair, hairy footed Hobbits who save the day along with the reminder that it was those tall, fair ones who were too proud and too power hungry to do so.

This is jumping ahead a bit but the scene where Sam sees the fallen Oliphant rider and instantly pities him, this warrior so exotic and unlike anything a simple hobbit has ever seen. Sam wonders what lies he was told to lure him to death on a battlefield, so far from home. Sam also pities the enslaved, magnificent beast turned war machine. I believ Sam is the true heart of the story.

But as for the battle itself- I never saw it as anything but heroic. A last stand against overwhelming odds- a never lose faith, search for the break of day- kind of victory.

Gimli, Legolas, and Aragorn were in fact giving their lives to help a beleaguered people. They could have made valid excuses to leave them to their fate-but didn’t. If G and L find a form of distraction from the almost certain, brutal death awaiting them, well, having never been faced with that, how can I judge them?

And remember they were the only thing between Orcs and a caveful of women and children.

The slaughter made sense to me, at least on later readings (I don’t think I thought about it much when I initially read it in 1967). Militarily, those Orcs and Men, had they lived, could have regrouped and fought again. Remember that the outcome of the war was in serious doubt. Theoden was leading what he thought was a suicide charge; he had little expectation that he or his men would survive.

MKUhlig @@@@@ #17 (And Kate) – “I don’t see why they built such a convenient ramp for the battering ram…”

I think the reason for the ramp is that despite occasionally having to take refuge in the fortress, their military heavily weighted to cavalry. Having easy access for a battering ram is the price to pay for being able to quickly get the horses in and out. Which is to say, I suppose, that the ramp is specifically to enable the charge at the end.

Kate @18: Tolkien realized later that by making the Orcs inherently evil he had written himself into a theological corner, and in his notes tried without success to resolve that matter while working within his established mythology. (But, as you say, more on that later.)

As nviner points out in #19, the vast majority of deaths in medieval battles of all periods came after one side broke and ran. Tolkien is being accurate here.

I would also suggest that the Norse sagas would have been an influence on the Gimli-Legolas contest. The Icelandic heroes chat all the time as they fight, usually making incredibly grim yet wry/ironic comments in response to individual blows or deaths.

As others have pointed out: if your goal is destroy a routed infantry army, using cavalry to ride it down is a very effective way to do it. Otherwise, you risk it forming again elsewhere. My reading is simply that of a sucessful cavalry attack while the enemy’s attention is focused elsewhere. After all, if the infantry doesn’t break and run, the potential is there for the cavalry to lose the huge advantage the horse’s momementum gives them and get pulled off their horses.

With reference to the Gimli-Legolas contest: I don’t think the intention was that of a light-hearted game. Like Rob Barrett@25 points out: a big part of a wide variety of martial myths can involve the champions of one side or the other and how many foes (and of what quality) they personally account for and how. In those myths and I think here in LotR as well, it’s meant to establish that yes, these particular people are exceptionally skilled and deadly warriors. In those traditions, when a skilled veteran is described, you don’t hear the more modern “they met every objective with a minimum of casualties”, it’s more like “they killed 15 in the skirmishes the last two years, including 3 at once in the battle at the gates”.

On a more practical note: I think Gimli’s total of 42 with an axe easily puts the run across Rohan to shame as a feat of endurance.

tapsi @@@@@ #3, the problem is that so far I’m not convinced that Orcs are inherently and indisputably evil. Gimli, at least, knows that they’re intelligent and have personalities.

I’m not convinced, either, but the characters in the book are, and if we are to judge their actions, that’s what matters. They know Orcs are intelligent and have personalities (I think Aragorn and Legolas know that, too), but intelligent beings with distinct personalities could still be thoroughly corrupt and evil. It’s hard to imagine a species that’s actually evil and not just alien, but the Orcs seem to be like that. I think the best feature we ever get to see an Orc display is the last stand of Uglúk, but they do not even help their comrades as humans would (see Sam and Frodo’s journey across Mordor).

I’m not saying I like it, but there’s nothing in the book that’d hint at anything noble or humane about Orcs as far as I remember. It’s a shame (and it’s far less intriguing than a race of Orcs fallen but redeemable would be) but that’s what evidence in the book shows and that’s what our heroes have to act on…

I found most interesting was the objection to ethnic and racial mixture that crops up. Not just the mixing of human ethnic groups (as between Rohirrim and Dunlending) but also the horror at the possibility that the “blood” of human and orc had been blended by Saruman.

As for Saruman’s experiments, part of the horror must be that their subjects were in all likelihood coerced.

sotgnomen@15

There’s more detail about the battles of the Fords of Isen in Unfinished Tales (specifically the chapter called “The Battles of the Fords of Isen”).

(My understanding is that the main text of this chapter is basically written by JRR Tolkien, with footnotes by both Christopher and JRR.)

Among other things, the chapter says that the reason the Fords were held until March 2 was that Saruman made two key errors:

1) In the first battle Saruman focused the attention of his army on killing Theodred to an extent that interfered with the conduct of the battle.

2) Not immediately following up the first battle with a full-scale invasion of Rohan.

(Tolkien does note that “the valour of Grimbold and Elfhelm contributed to his delay.”)

Kate @18

Ghân-buri-Ghân and his people help the Riders travel the backwoods trails behind the beacon hills (Min-rimmon, Eilenach, et al) to arrive at the Pelennor Fields without being spotted. On the Riders’ return, as a reward, heralds proclaim that the hills belong to GbG and his people.

It isn’t in the Appendices, it’s in Book V.

Re: the nature metaphor,

Sometime around when the movies were coming out, I read somewhere that a big part of the series was about nature (represented by the Hobbits most of all, with their peaceful farming ways) vs industry (represented by the orcs, and the machines of Saruman, and so on).

The movie, especially the two towers, made me feel that even more strongly than the books.

I wish I could track down the analysis of the whole series that way! Perhaps this one

http://tinyurl.com/LoTRnature

or

http://www.bookrags.com/research/tolkien-j-r-r-este-0001_0004_0/

I’d love to hear more commentary on that issue (particularly whether this is one of the main metaphors or motivations for the whole story).

If I might butt in here – I read some books last year on the Second World War in the Mediterranean basin, particularly in Greece and North Africa, focusing on the ANZACs – the Australians and the New Zealanders who fought the Deutsche Afrika Korps.

It strikes me that Tolkien’s military training would’ve included the inevitable bayonet charge. And bayonet charges are neither pretty, nor intended to be. The ANZACs shattered the nerve of a crack Alpine force during the Battle of Crete by making one such bayonet charge along “42nd Street”, to give it its “official” military designation.

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2-23Ba-c5.html

http://www.mlahanas.de/Greece/History/BattleOfCrete.html

http://www.28maoribattalion.org.nz/story-of-the-28th/greece-and-crete

And the New Zealand Division in North Africa made themselves infamous during a breakout at Minqar Qa’im during the see-saw battle for North Africa between the British Army and the DAK:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_history_of_New_Zealand_during_World_War_II

This is the sort of thing Tolkien did know about. And it is an effective way to win a battle. So naturally the Rohirrim used its horse-borne equivalent.

As for orcs being irredeemably evil, I think Tolkien had the final word on that in The Book of Lost Tales, where he talks about the Druedain and the orcs being kin, and regarding each other as renegades. Tolkien never did get his story sorted out about the origin of the orcs: I always took the Silmarillion tale about them – distorted and tortured and ultimately innocent-of-all-but-their-own-evil-and-stupidity Avari relics of Utumno’s torture chambers.

Kate, I think the fighter pilot thing is apposite. True, it was combat at a distance — but fighter pilots were most assuredly ranked by their number of kills.

We remember the Red Baron today because he achieved the highest number of any of them. And while the other aces of the era have been largely forgotten, in the 1940s they were still household names. Schoolchildren were still taught who the “greatest” fighter pilots of the last war were — and “greatest” was firmly defined by how many foes they’d shot down.

I’d also add that Tolkein probably saw things much, much more extreme than this in the trenches of the Somme. I’d agree with DBratman (#11) that while Tolkein doesn’t glorify war, he doesn’t believe in fighting half-heartedly either.

Doug M.

One other thing: ISTR that this had one of the very few references that could be traced to Tolkein’s time in Africa. The term “strawhead”, used by the Dunlendings, was apparently a racial epithet used by natives to refer to white settlers.

I’d hesitate to suggest that the Dunlendings were Zulus or whatever, but it does shed an interesting light on the fictional history.

Doug M.

Kate, your comments make me think you may not believe in the reality of heroism in any battle, ever?

The courage of Théoden and the rest of the defenders’ final charge always brings a lump to my throat. I think it captures heroism in battle exactly.

Can you imagine how many times Tolkien saw comrades fling themselves “over the top” of the trenches in desperate but heroic futility? The generals on both sides of the trench warfare were idiots and worse for keeping it up for so long, but the men’s sacrifices affect me all the more for their tragic devotion to their duty.

How do we value those sacrifices? Very heavy question. And not one to be answered in comments on a website, I reckon. Each of us brings our own perspective, and I will respect others’. As for me, I do believe in heroism in war, as I also recognize there is always a great deal – and sometimes overwhelmingly too much – of bestial behavior that accompanies warfare and its aftermath.

War is very bad, but sometimes the alternative is worse.

Like, for example, when a demigod raises an army of monsters to come eat us and our families and our allies. Then we fight! And yes, glory in each dead monster. (And live with the nightmares later, perhaps.)

I believe the further development of background on the Druedain and their Numenorian background is in The Unfinished Tales–and I believe Tolkien was still developing this toward the end of his life– giving them a Numenorian background was a late development in his world building, if I’m remembering Christopher Tolkien’s comments properly. I like to think JRR was grappling with some of his racist descriptions in LotR in developing the Druedain further and starting to complicate them beyond the noble savage template–the tale was still growing with the teller over time.

The hostility of the Dunlending’s ancestors towards Gondor started when Aldarion, the first Ship king of Numenor started cutting down trees to build a Numenorian fleet and making settlements along the coast and pushed the Dunlendings ancestors out. Sauron stirred up their hostility to the Numernorians, but Tolkien does complicate this by giving us reason to sympathize with their displacement and the logging of their trees–I don’t think I’m applying an anti-colonialist template here without some encouragement from Tolkien’s telling.

In part, Aldarion is building this fleet to aid the Eldar in their resistance, but the resistance of the Eldar is of course always problematic since they resisted the Valar to try to retrieve Feanor’s problematic works of technology from Melkor. And the Valar are fallible. No one has the total moral high ground here. Part of Erendis’s conflct with her husband Aldarion is over her love of trees and his love of maritime exploration built on the timber of destroyed trees, and Tolkien does not resolve the conflict or make it one-sided. In light of this history, it’s ironic that the Ents and Huorns wind up supporting Gondor and its allies, but only because Saruman is the more pressing danger for them at this point in the history of Arda.

The history of Numenorians in ME is as a colonizing power. It’s complicated, though, in that the Numenorians and Noldor in ME have their origins in ME, not in Numenor and Valinor, and are acting as reinforcements to peoples still in ME as much as a colonizing force, and yes, it’s as complicated as the region in our earth we label with the initials ME.

I’ve never liked these battle portions of TTT very much and haven’t reread them in a while–least loved parts of the LotR for me.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Black_Book_of_Arda provides a brief description of The Black Book of Arda and a related writing.

One of the things that makes it a harder read than some of the other chapters, while at the same time a more powerful read, is the desperation of the Rohirrim.

Their choice is starkly simple: fight or die.

The historical analog for the Dunlendings that springs to my mind most readily is the Celtic peoples who were displaced by the Angles and Saxons.

Was there ever, in the history of nations, a nation that was not built on the ashes and bones of those who were there before them? (Perhaps I exaggerate but only a little, I think.) I do not think Tolkien was advocating or excusing anything. I like the comment about complexity and realism, also the non-Sauron conflict(s) that are exploited by him. This is a theme in the Silmarillion as well, that sometimes earlier bad behavior sets the stage for a fatal weakness. The Rohirrim are more fortunate than say, the Sindar of Doriath in that respect.

Interesting Commentary – I googled Helms Deep while reading to see the map – saw a bunch of very good illustrations and a wargamers diarama – which helped a lot in understanding. In past reading, I always saw the Hornburg as facing East. I was all messed up facing North and having to switch it all around in my head. Pictures help.

Dunlanders and the 500 year grudge – I’m American (we have been here about 350 years). The Natives may have a grudge against all of us who brought disease, killed most of them off and then placed them on reservations, but in today’s time, can they point at a single enemy and target them. The geography is different in Rohan – much smaller and more like Europe in scope – but I still have a problem with it. I am also not a Kurd in Northern Iraq and not a diasporic Jew. All of this contradicts my thought that it shouldn’t matter. I guess it does. I personally have trouble holding a grudge for more than a week, so I don’t always get it.

Leaders – I am struck by the caliber of leadership in Theoden. What King can call a scout out by name (he rules a cavalry of over 10,000) – and after being basically invalid for the past years no thanks to Wormtongue. Then leading the Charge – Desparate and Kamikaze-like? YES – Seemed Silly at the time that the once and Future King Aragorn would help in a suicide charge – given his past and his plans for the future, but it is at times like this that leaders are born.

But Comparing the leaders throughout Middle Earth, I would choose Theoden as my king.

Also, for the Charge – This time, as in all the others, the description of the sound of the horns in the Deep brought chills and tears. Great Great visualization.

NOW for a Challenge – little bit of a threadjack: Some people hate this battle. Others love it. This series has 3 epic battles – Helms Deep, The Pelennor and the Black Gate. All have their Merits. My Vote is for the Pelennor as the best. HOW do these compare to other Epic battles throughout literature – fantasy or otherwise. Anyone want to offer thoughts – Book, Battle

Elfstone of Shannara – Bad ending, but the battle defending the tree was Epic – loved the cavalry descriptions.

Les Miserables – Waterloo – best description of bloody awful war – and battle tactics and how they failed.

Hi, all.

Re: the last charge: I can see that it would be militarily advisable and historically accurate, but the very high-fantasy, glorious, no-blood-or-cost-to-be-seen language remains incongruous to me.

Fledgist @@@@@ #20, I agree with tapsi @@@@@ #27 that with the specific case of Men (sic) & Orcs, the element of humans being used as nonconsenting experiment subjects adds to the horror, but that doesn’t account for all the other times in the book when mixing is bad. (One of these days I’ll come up with a coherent rationale for when it’s good and when it’s not. Is it significant that all of the elf-human marriages are Elven women & human men, perhaps? For some reason I thought women married up, not men.)

SusanJames @@@@@ #21, that’s very interesting about Gimli and Legolas using the game as distraction. I absolutely did not get that impression from the text or my overall sense of their characters, but it’s something to think about.

Jon Meltzer @@@@@ #24, as far the theological corner re: the Orcs, if Tolkien couldn’t resolve it I doubt I can either, at least within the limits of the text, but it is worth talking about.

mikeda @@@@@ #28, thanks for reporting on the battles at the fords.

sps49 @@@@@ #29, I remember that about Ghan-buri-Ghan’s appearance in Book V, just not the history that Michael S. Schiffer alludes to.

Aladdin_Sane @@@@@ #31, I think Tolkien had the final word on that in The Book of Lost Tales, where he talks about the Druedain and the orcs being kin, and regarding each other as renegades. Tolkien never did get his story sorted out about the origin of the orcs

Goodness I’m glad he didn’t make the Druedain relatives of the Orcs. Wow.

Doug M. @@@@@ #33, I did not know that about “strawhead.” Thanks.

PHSchmidt @@@@@ #34, I do believe in the reality of heroism during battle. I just would locate it and describe it differently.

lavendertook @@@@@ #35, anything that involves cutting down trees is definitely a big sign of where Tolkien’s sympathies are. => Thanks for the information.

Marc Rikmenspoel @@@@@ #36, re: The Black Book of Arda: I’m glad that I’m not the only who thought that Melkor & Feanor’s falls were somewhat problematic . . .

sunjah @@@@@ #38: Was there ever, in the history of nations, a nation that was not built on the ashes and bones of those who were there before them?

That topic is outside my expertise, but I do want to note that the answer to your question, of course, will depend on how you define “nation,” which is a pretty recent concept after all.

alfoss1540 @@@@@ #39, good point about Theoden’s leadership skills. I really don’t remember the other epic battles in this book well enough, or really most others because I have rotten visualization skills. The exception is of ship actions in Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin novels, because those I listen to on audiobook first! (And there’s twenty books’ worth of those so it’s very hard to pick.)

There was one instance of elf man, human woman – I guess it would be “affair”, because there was no marriage: Aegnor and Andreth, in the First Age. He dumped her, but he felt Really Bad about that.

Is it significant that all of the elf-human marriages are Elven women & human men, perhaps? For some reason I thought women married up, not men.

I think it’s simply because Tolkien was a man and he idolized his “lady”. It seems to me that he held the old romantic view that women had to be more “heavenly” than men to inspire lasting love.

As for men marrying up, it happens in a lot of fairy/folk tales: cunning shepherds get the princesses, mortal princes wed fairy queens… Cinderella’s probably the only counterexample I recall right now.

Is it significant that all of the elf-human marriages are Elven women & human men, perhaps? For some reason I thought women married up, not men

I think it’s simply that Tolkien didn’t have many (any?) wandering female Edain heroes combined with a lack of cultures where the woman could “win the hand” of the man. Beren, Tuor and Aragorn all had to complete some pretty exceptional deeds _AND_ win the heart of the woman after all.

We also have the sole elf-maia intermarriage, Thingol and Melian.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dr%C3%BAedain has the basic story of the druedain.

I cant remember which book it was, thinking maybe unfinished tales, that had a short-story on the druedain. It said that they lived in the forest of brethil, and some of them took service with the hadalin(the blond guys that the rohirrim are said to descend from, you’ll notice)

The story was about one household of haladin who had a druadan living with them. He carved a pukel-statue outside their house, to protect them whenever he was away. One night when he was gone, orcs attacked the house and set fire to it. They were stopped by the statue coming to life, killing the orcs and trempling the flames. When the druadan returned, they noticed he had bandages covering his feet.

Allways thought that was one of the more beautiful stories in the mythology, and it got me wondering what history there was between the druedain and the haladin, to make them stay close to the rohirrim and help them, even though they were forgotten, and reviled in later times.

The whole story fits in with the theme of sadness and estrangement in lotr.

I noticed the nature imagery in this battle and the other major set-piece battles, too, and I commented on it in my book _War in the Works of J.R.R. Tolkien_. There are a number of poems from WWI that use nature imagery in a sardonic way to describe battle — notably Blunden’s poem “Rural Economy,” in which grenades are “iron seeds” and so on. But I don’t think this is what Tolkien was doing here, precisely; I think he may have been more interested in the contrast between more “natural” primitive warfare and the more mechanized aspect of modern warfare, as represented by Saruman in particular. However, and this is the really interesting bit — pay close attention to the skirmishes in “The Scouring of the Shire.” There’s no nature imagery there, just straightforward _reporting_.

Post-WorldCon catchup:

Jon Meltzer @@@@@ #41, I have no memory whatsoever of Aegnor and Andreth. The Internet suggests that this is because they aren’t in the _Silmarillion_, so I feel a bit better about that.

Good points about the marrying up in fairy tales and in _LotR_, all, thanks. I was thinking in a different context.

Janet Croft @@@@@ #46, I will definitely be paying attention to the continued imagery used in describing battles–what you say about the Scouring is very interesting and I’m already theorizing about it, months ahead of us getting there!

Aegnor and Andreth are in Morgoth’s Ring. And, yes, the Druedain stuff is in Unfinished Tales. There’s a lot of good and interesting stuff hiding in all those volumes.

tapsi@42: And it’s doubtful, indeed, to what extent Cinderella did marry up. She wasn’t a princess, it’s true, but she was a noblewoman.

On the Dunlanders: I was a bit puzzled when I first saw this discussion, because I had never thought of the Dunlanders as natives of the area which became Rohan. So I checked it out in the appendices, and this is what I came up with. According to the section about the Rohirrim, the land was empty when they took it over; most of the previous inhabitants had been killed in a plague, and the remainder in the invasion which the Rohirrim helped to repel. The section about the Dunlanders adds to this that they were cousins of people who had previously lived in the valleys of the White Mountains, from whom the Dead of Dunharrow came, but the ancestors of the Dunlanders had moved west to the southern valleys of the Misty Mountains, apparently before the Rohirrim arrived. So while the statement that ‘once their language was spoken in many western valleys of the Mark’ might well be taken to imply that they had been dispossessed of these areas, I don’t think it does mean that; they had left of their own accord; their cousins, who stayed behind, had been destroyed. One might well think that gives them some kind of right to the land; certainly it accounts for their thinking it; but it’s not clear-cut.

(On Aegnor and Andreth: insert complaint about HoME being taken as telling us what really happened.)

Marc Rikmenspoel…I had to comment regarding your love of this part of the LotR. I find your asseration you feel the rest of the story supporst this moment amusing. In the Letters of JRR Tolkien, you will find that Tolkien never even wanted the battle of Helm’s Deep. He did everything he could to downplay it because he felt the true and most important battles of LotR are Minas Tirith/Pelenor Fields and the Battle before the Black Gate. So I have to admit, you comment made me smile.

I guess in the end you can attribute this as the mark of masterful writing…knowing what the story needs and doing it well…even if you the author aren’t quite sure. As Tolkien said time and time again, the story took on its own life…as seen with the entry of Strider, Bombadil and Faramir to name a few.

As to Gimli and Legolas’s rather grim game…I think it’s drawn from old notions of honor in battle. The orcs (and Dunlendings) being evil in their eyes, it is seen as a great acheivement and sign of prowess to have killed them. Often such numbers became part of the warrior/knights weapon or armor decoration. It was a way to demonstrate their own skills, as well as (in a perverse way) honor the dead.

The final charge of the Rohirrim is an act of desperation. They are severely outnumbered. In such cases they’d take whatever advantages possible. Plus, as others have stated, the uruk hai were concidered evil and irredeemable…

Something I first noticed this read through was the juxtaposition of Gimli and Legolas’ comments to each other regarding Fangorn and Helm’s deep. In the White Rider Gimli says of Legolas’s positive comments on Fangorn:

“Your are a wood-elf anyway, though elves of any sort are strange folk. Yet you confort me.”

In this chapter Legolas say of Gimli’s comments on Helm’s Deep:

“…you are a dwarf, and dwarves are strange folk. I do not like this place, and I shall like it no more by the light of day. But you comfort me Gimli…”

Its a small thing, but I like the way Tolkien interweaves these scenes, and I like the implications this reversal has for the development of the relationship between Gimli and Legolas.

“Second, again we have my approaching the text from a completely different perspective than Tolkien. Because you say “someone who didn’t live here gave the land away to newcomers” and I say “colonialism, imperialism, and the oppression, forced displacement, and genocide of native peoples.” In other words, I doubt that the text wants me to sympathize with the Dunlanders—no-one in this chapter, at least, acknowledges that they have a legitimate reason to be upset—but you bet I do.”

I see what you’re saying, but the problem with this is that the Dunlendings are not native–not even in the sense that American Indians are native, having crossed over long ago from another place. The Dunlendings did not reach the Mark before the Rohirrim, then called the Éothéod.

That’s half of it but there’s another part too. The Dunlendings did not think, “Screw Gondor for thinking they could give away the Mark to the Éothéod.” Their thought process was more akin to, “Why did they not give it to US?” There is an understanding in all of Tolkien’s work that a higher power must always appoint you to have stewardship, or kingship, over anything. The Dunlendings don’t dispute this fact; rather they’re enraged that they weren’t chosen. Which, of course, is silly–the Éothéod weren’t CHOSEN. They earned it, by coming to Gondor’s aid at the time of need.

joyceman @@@@@ #51, that is lovely. Thank you.

Jakkblades @@@@@ #52, yes, that’s been discussed some, but IIRC, you couldn’t tell that from this chapter, and I hadn’t remembered it from the Appendices.

I’m slightly surprised that there’s very little comment on the use of language in this chapter. The scene where Theoden and Aragorn ride out against the orc army is almost poetry in the way it reads. I love the use of sentence lengths and slight repetition of words to really drive the text forward.

Judith, it’s the kind of thing I often talked about in other chapters, but I think I must’ve just had too much on my plate here. For my next (personal! => ) re-read I will keep it in mind, though.